Jacob Boehme (1575-1624) was a simple shoemaker of Görlitz, Silesia (now part of Saxony, Eastern Germany) who has had an enduring influence within the path of what may be termed as inner alchemy. Historically, he occupied a significant position and can be seen as a bridge, or conduit, from a Germanic period of mysticism – referred to as Rhineland mysticism – that included Meister Eckhart (1260-1328) and his disciples Henry Suso and John Tauler. The Rhineland mystics were a late medieval Christian mystical movement which consisted, largely, of Dominican monks or at least figures well-placed within Christian theology. Boehme, in contrast, was neither a monk, a preacher, or anyone of theological status – he was a simple artisan who had no formal education. He was also a family man. The point to note here is that Boehme represented the ‘Everyman’ and as such also represented the individual ‘direct’ path to access divine consciousness. In this way, he is often seen as part of the lineage referred to as inner alchemy, or the Golden Thread.

It can be said that Boehme was ‘chosen’ to impart profound mysteries at a time of growing theological scholasticism. Boehme is now described as a ‘philosopher’ and a Lutheran Protestant theologian, yet these are largely modern classifications that do not do justice to his revelatory nature. At heart, Boehme was an individualist who gained his insight from personal visions. That he was immersed within a world of Christian theology should not detract from the uniqueness of his presence. He was, and remains, an outsider to the mainstream theological traditions – as is the case with most, if not all, genuine mystics.

The original revelation that Boehme received in 1600 is now famous. It consisted of a vision whilst concentrating on the beauty of light as it reflected off a pewter dish. In keeping with many visionary triggers, it was an event that placed Boehme’s consciousness into an altered state of perception. In this state, Boehme claimed that he ‘saw’ the spiritual structure of the world, as well as the relationship between the Divine and Man, and between Good and Evil. It proved to be a vision that not only changed his life but also set him on his path that engaged him for the rest of his life and produced a series of well-known treatises and writings.

Boehme’s writings reveal a way to understand the divine relationship beyond that of rituals, sacraments, and scriptural theology. What he revealed was also an inner reality that could be more real than any of these outer garments. As Boehme related of his vision in 1600 – ‘in that quarter hour I saw and learnt more than if I had studied many years in some university…for I perceived and recognized the Being of all beings.’ It is no accident that an artisan of no formal education or theological rank should be gifted such gnosis, or inner knowledge. Without doubt, this put him in direct conflict with the religious authorities of his time (as it did with Gregorius Richter, the pastor of Görlitz who accused Boehme of heresy).

The writings and visions of Jacob Boehme are now seen as forming a path of Christian theosophy, as distinct from Christian mysticism. The main point of distinction here is that theosophy is recognized as an experiential path and not only of the intellect. It speaks also through emotional, or bodily knowledge, upon such subjects as metaphysics and cosmology. It is felt and lived, not only mentalized. Boehme understood his visions because he felt and lived them as well as seeing them (with the inner eye). It was also a reaction to the rising theocracy and hierarchy of religious institutions at the time. In this respect, Boehme was followed by later Christian theosophers such as Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (1743-1802), and Karl von Eckartshausen (1752-1803, author of the famous mystical work The Cloud Upon the Sanctuary).

The writings and visions of Jacob Boehme are now seen as forming a path of Christian theosophy, as distinct from Christian mysticism. The main point of distinction here is that theosophy is recognized as an experiential path and not only of the intellect. It speaks also through emotional, or bodily knowledge, upon such subjects as metaphysics and cosmology. It is felt and lived, not only mentalized. Boehme understood his visions because he felt and lived them as well as seeing them (with the inner eye). It was also a reaction to the rising theocracy and hierarchy of religious institutions at the time. In this respect, Boehme was followed by later Christian theosophers such as Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (1743-1802), and Karl von Eckartshausen (1752-1803, author of the famous mystical work The Cloud Upon the Sanctuary).

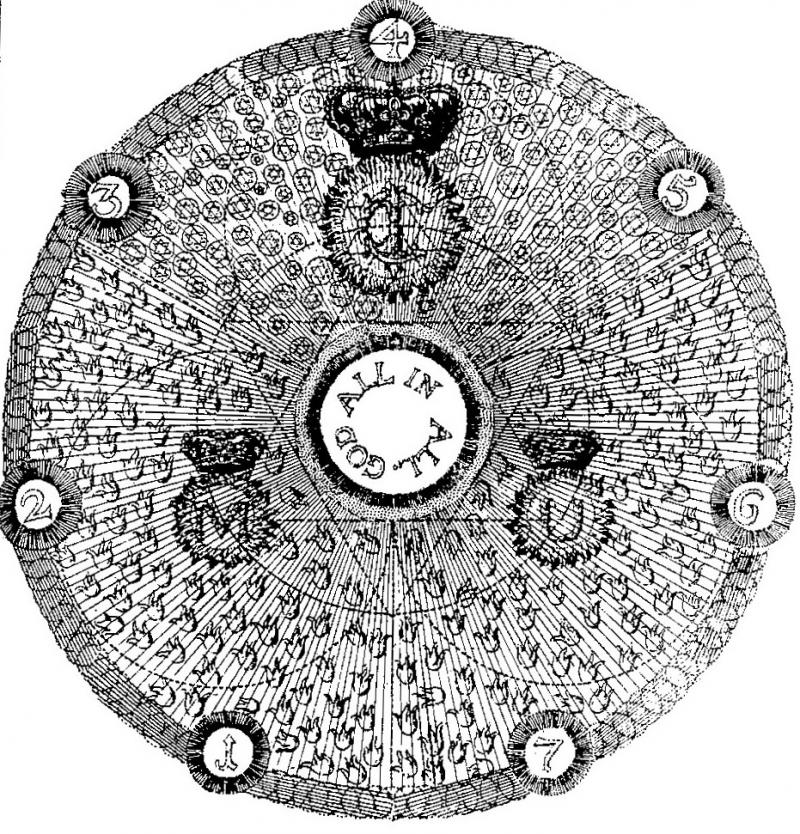

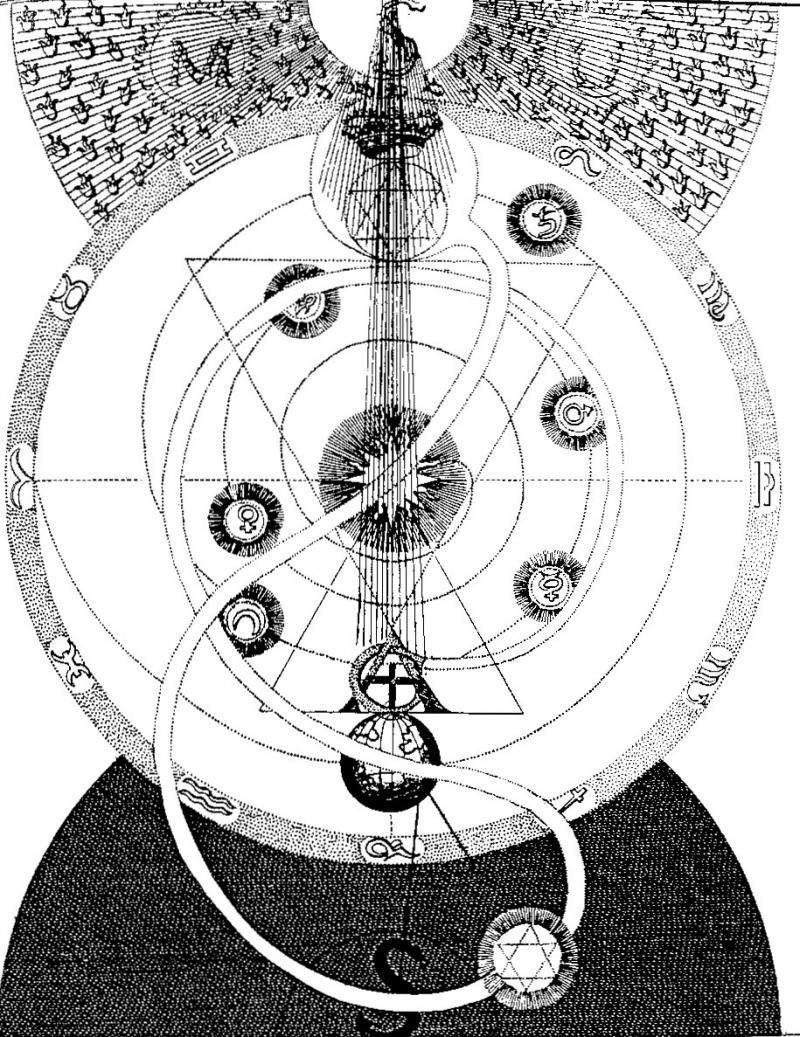

As stated, Boehme’s theosophy represented a path of inner gnosis where the human being enters a transcendent way of knowledge. The person becomes a participant within the Divine, sacred cosmology. They are not bystanders or philosophical onlookers. It is a path of immersion. As such, it is not necessary, or even important, that a person be theologically motivated or religiously trained. Sometimes this can itself be a hindrance. Yet the framework of Christianity – or in Boehme’s case Lutheran Protestantism – gave him a language (a set of tools, if you will) in which he could transmit his knowledge and cosmology. Such tools often change from era to era. In fact, the physicist Basarab Nicolescu recently demonstrated the parallels between Boehme’s cosmology and quantum physics. This is a recognition that there is no discrepancy between modern science and metaphysical knowledge. Boehme was a beacon of inner light within a world of theological scholasticism.

The influence of Jacob Boehme has spread far and wide. He has become more well-known now than he was in his time, which is a common pattern. The line of Christian theosophy continues to this day as a strong current within Western esotericism. Those that follow Boehme’s teachings group themselves as Behmenists (from the English pronunciation of his surname). Behmenist groups exist across Europe, including the Netherlands and England, as well as existing in America. In England, Boehme’s legacy was carried on by John Pordage and Jane Leade who established the Philadelphian Society in 1670. Such a path is largely an inward one, and people may follow it with or without the influence of Jacob Boehme. In some ways, it can be seen that Christian theosophy had correspondences with the alchemical path of its day. Both spiritual paths take place within the crucible of the human body-soul. Boehme’s revelations were a mix of alchemical, gnostic, and mystical insight that were expressed in a style that modern readers today may find difficult.

Whilst his books are less read these days, Boehme is perhaps recognized more through the influence he has had. Some commentators consider Boehme as the founder of modern Christian theosophy (which is distinctly different from the branch of theosophy attributed to Madame Blavatsky). Boehme’s writings went on to influence such notables as William Blake, C.G. Jung, Martin Buber, Coleridge, Hegel, Schelling, Heidegger, amongst others.

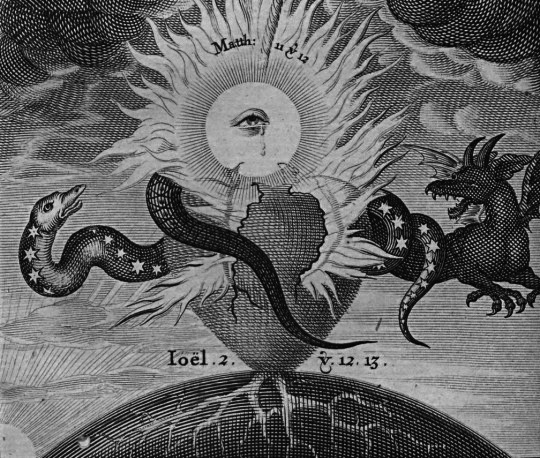

Boehme’s vision was fundamentally Christian although much of his cosmology was expressed in alchemical terms which required attentive reading to comprehend. At the heart of his vision are the archetypal struggle of forces between Goodness and Evil, and the forces that hinder Humankind’s evolutionary struggle toward reunification with the Divine. The great universal struggle takes place also within the very being of each person. This also reflects the alchemical process towards inner purification and spiritual regeneration. Boehme, in a form similar to Hermeticism, recognized that opposing forces are operating through the microcosm as well as the macrocosm.

The greatness of Jacob Boehme also lies in the fact that he offered the world a vision of reality that was far ahead of his time. In that, he was a spiritual innovator. He gifted the world a vision of a dramatic, evolving spiritual reality that operated not only within the divine realm but also through the human being. In this, Boehme was the cosmic cobbler par excellence.

Solomon James

September 2019

Available on Amazon, click on the book: