Late medieval Europe was blessed with a number of important religious thinkers who enlivened the austere Aristotlism of past scholastic writers. Men such as Meister Eckhart, John Tauler, and mystics such as Julian of Norwich and Walter Hilton helped to leaven a Christianity that was in danger of becoming reduced to an arid analysis of dogma for its own sake. This new generation of writers, however, helped to breathe fresh life into a moribund system of belief that threatened to diminish Christ’s importance for laymen and cleric alike. One of the most important of these thinkers of the fourteenth-century was John of Ruusbroec whose books, The Sparkling Stone and The Book of Supreme Truth, reflect a re-invigorated emphasis upon the works of Dionysius the Areopagite and Boethius from an earlier age, and their commitment to giving expression to the mystical life as a viable spiritual practice.

Some men are born into such a life, never doubting their vocation even as children. Ruusbroec was such a man. Born in 1293 in the tiny village of Ruusbroec, not far from Brussels, we know little of his early life other than that he was brought up by his mother. According to one chronicler, he was strong-willed, adventurous and insubordinate. At the same time he was afflicted by a strange restlessness, as if there was something forever on his mind. At eleven he ran away from home. In Brussels he sought out his uncle, John Hinckaert, a canon at the cathedral of St. Gudule, who took young Ruusbroec into his monastery of two in the shadow of the cathedral walls, where he lived with his friend, Francis von Coudenberg, practicing the ascetical life. Together, the three of them began a collective life as monastics. John’s of Ruusbroec’s spiritual education began early under the guidance of Hinckaert and his friend.

By 1343 the three men had left Brussels where they had conducted pastoral work, in a bid to set up a small hermitage in Groenendaal to the south. A number of other men joined them and, after local pressure directed towards them, they decided to accept the rule of St. Augustine in place of their less structured and more reclusive existence. Ruusbroec became the first prior, and his old friend Francis the first provost. At Groenendaal monastery, Ruusbroec continued his lifelong practice of writing mystical treatises, which he had begun to write in Brussels. His reputation grew. Men of like mind such as Geert Grote (1340-1384) and another great mystical thinker already alluded to, John Tauler (1300-1361), who both figured in the growth of the Modern Devotion movement in Germany and the Netherlands, visited their Brabantine retreat for spiritual guidance and council. Often, even in old age, Ruusbroec would set out on long walks from Groenendaal to council people in their spiritual life. He died peacefully in December 1381 surrounded by his brethren.

The priory of Groenendaal lay in a forest. For John of Ruusbroec it was a perfect place to refine his devotions and cultivate his inner life. Other than when hunters came to the gates asking for food or a bed for the night, the priory enjoyed its silence. It is said that the trees became Ruusbroec’s friends. He spent many hours among them, and often recited his treatises to a scribe while sitting by a tree trunk. His biographer records how he was discovered by one of the brothers seated under a tree, rapt in ecstasy, surrounded by an ‘aura of radiant light.’ The fruit of his meditations, it seems, thrived upon the interaction between himself and the woods.

A simple life, a peaceful death. These facts sum up the uneventful nature of John’s life. If it were not for his many treatises he might well have escaped our notice. Yet he was no ordinary man. He lived at a time when much of Europe was experiencing a terrible pestilence, the spread of the bubonic plague. The disease had arrived in the Brabantine region around 1348 to begin its deadly decimation of agricultural communities, as well as its cities. By the late fourteenth century plague victims were already being depicted in illuminated manuscripts, asking for protection from their bishops. Half of the population of Paris (100,000), for example, died from the plague. To combat its effects, people resorted to astrology or the killing of Jews. The pandemic had reduced people to fear and loathing, to a sense that God was angry with their dissolute ways. Carts filled with bodies became a normal occurrence of a morning as these were being taken away for mass burial.

John’s writings give no sense of any crisis near at hand, however. It was as if the world beyond the forest did not exist, at least not in his immediate thoughts. He attended mass, he meditated and he wrote. He became, in his own words, a ghostly man. Moreover, in his writings, he forsook Latin to write in his native Flemish, a genuine departure. Like Francis of Assisi, Jacapone di Todi, and Richard Rolle before him, the people’s speech became his mode of communication. Vernacular not literary language was to be his vehicle of choice from hereon. Moreover, he realized that the old forms of literary structure could no longer contain the sublimity of his thought. He had to find another way of expressing himself. Images, not explanations, became the new order of the day for him, in spite of his ambivalence towards them. In using these as the substrate of his thought, he wrote, ‘this green valley, the humble heart…becomes brighter and more illuminated.’

From this point onward, we find ourselves in a northern forest. Ruusbroec’s mystical mind has become an extension to trees, to the fields, to nature itself. As he later wrote:

Pay attention to the wise bee, which gathers in the unity of its society and travels forth. Not in storms but in still, quiet weather and in sunshine, in order to visit all the blossoms where sweetness can be found. It never rests on any blossom, nor on any beauty or sweetness for very long. There it extracts from the bloom honey and wax – that is, the very sweetness and matter of illumination. Then the bee brings back what it has gathered to the assembled unity of other bees so that they might become fruitful…. The wise person should be as a bee, and fly with attention and with reason… and so taste the multiplicity of all consolation and goodness.

These are clearly the words of an observant man who loves the outdoors, and who sees nature as his book. For him, sapiential knowledge lies in a field of flowers or a babbling brook. He allows nature to teach him how to fashion correspondences that help him to bridge the gap between nature’s innate wisdom and his own attempts at detailing the mystical impressions that he experiences.

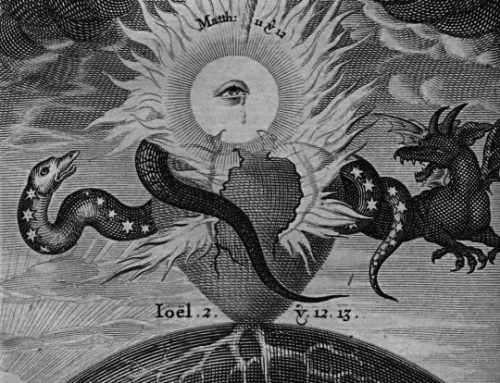

Let us, then, gather for a brief moment in the forecourt of his thought. Here is a man who allowed the ‘bright sun’ of Christ to enliven the ‘dawn’ of his mother, Mary. The loveable sun of Christ ‘flashed and shone yet brighter’ with the fullness of all grace and all gifts. Moreover, Jesus was also the ‘spotless lily and the common field flower’ from which, supposedly, honey is drawn forth in order to bestow its sweetness. Christ is also a ‘simple light’ that penetrates a person, steadying him and helping him to sustain an inward unity of spirit and mind, by presenting himself as an avataric presence in his, John’s, life.

John’s dilemma is how to reconcile his understanding of the unity of deity on the one hand, with the natural multiplicity derived from manifestation on the other. By attempting to resolve this polarity at a mystical level, he is then able to declare what happens, inwardly, to a person who has made peace with such a dichotomy. ‘A man is lifted up into a new state, and he turns inwards and focuses his memory on bareness, above all eruptions of sensible images, and above multiplicity,’ he wrote in the Espousals. Here we see John struggling to give up his dependence upon images, in all their multiplicity, in his dogged pursuit of a supernatural inclination towards unity. Influenced as he is by Dionysius of Areopagite’s negative theology – that is, towards eliminating any statement about what is – John of Ruusbroec finds himself exploring the concept of bareness and denudation of the sensible image. For a moment, it seems, flowers and trees and bees have become an impediment to laying bare what he calls the ‘incomprehensible richness and sublimity, the outflowing, generous, and unique commonness of the divine nature.’ Only this fact, this richness and sublimity of the divine nature, however, when it is clothed in images, can lead a person towards what he asserts is a state of pure ‘astonishment.’ That is, a onefoldedness in its very multiplicity. Such a vision of unity in astonishment, John seems to be saying, opens the door to an ever-deeper vision of what lies beyond the perception of the image.

John is taking us on a journey towards a ‘one-fold clarity’ where time and space no longer exist. Motion and change are suspended. Such a clarity stands outside the capacity of the faculties to give it form. The essence of the soul has become a spiritual kingdom filled with divine clarity. Only an understanding of onefoldedness can begin to make comprehensible the unity of our spirit with the supra-essential unity of the Divine. John is struggling now, and we can feel it. He has proposed the existence of a ‘one-fold’ nature which he sees as a form of eternal complacency, none other than a passivity in the presence of deity, which leads to a fathomless love of Being. Once more we find ourselves in the domain of antithesis and the need to reconcile polarities, which is the final resort of a mystical thinker.

Where else can one go? Beyond the metaphor, John seems to be saying, even though he himself was forced to use them often in his work. He is subject to a ghostly wound, a wound that he knows resides in his soul. Yet this wound pens the way for oneness to streams into his heart, in spite of the pain it causes. Only then can the ‘quotidian fever’ of multiplicity be neutralized. The dazzling splendor of the image must somehow be overcome. Even the faculty for making them in the first place must be put aside. What was once an ‘unspotted lily amidst the flowers of the field’ must be torn up by its roots from the imagination. John is looking for the abyssal and unconditioned Good which would otherwise be reduced, or clouded by images. In the end, he has to admit defeat. ‘We must use sensible images,’ he cries out at last, ‘diverse similitudes and images.’ Only these can give shape to differentiation, he finally admits, which is the final preserve of Godhead even in Its onefoldedness. John of Ruusbroec has been brought down to earth by his need to articulate divine absence with the only tool at his disposal, his imaginal intellect.

I try to walk in the woods with John and see what he sees. There are pine cones, lichens, flowers, broken boughs and fungus growing on tree trunks. There are feathers from birds, the skeletons of insects, nests in trees. These are what he sees; they are ordinary things, the repost of the earth going through the motions of stability and growth all at once. How can he extract from simple things a transcendent landscape? I ask myself this question because I want to know how to manipulate the sensible image into the making of what he calls a ‘supernal stillness.’ This is a condition that stands above all creatures, and yet infuses them at the same time. The reflexive nature of divinity, in that it eludes conceptual analysis, yet finds a way to dally among things, is key to John of Ruusbroec’s mystical way of thinking.

At one point he speaks of Christ’s touch. This touch invites our spirit to explore the most inward practices in order to emulate ‘in a creaturely way’ the created light that is Christ in his humanity. The spirit, through the power of love, raises itself above all works, ‘into the unity where this life-giving spring or touch, gushes forth.’ Such a touch, according to John, invites a man to know God in ‘His brightness.’ So God abides alone in his inborn radiance. Those who have pierced through ‘their ground,’ to their very source by way of inward practices, they alone are able to feel Christ’s touch and thus ‘see’ His Light. When a person has felt His touch, then in Him ‘love goes forward, while understanding stays outside.’ John is asking us to believe that understanding is not fruition, that fruition lies more in ‘tasting and feeling’ than in understanding. At once we begin to know: the faculties have their limit, but are necessary for allowing the depth of divine love to come to rest ‘inside’ understanding itself.

John further maintains that all our senses become involved. Touch, for example, delivers empathy, not craving, to the hungry man. In the Espousals he elaborates what he means:

God’s touch and His gifts, our loving craving and our giving in return, keep love steadfast. This flowing-out and flowing-back causes the fountain of love to overflow. Thus God’s touch and our love’s craving become one single love. Here a person is so possessed by love that he must forget himself and God (our ital.), for he knows nothing but love. The spirit is burned up in the fire of love, and it goes so deeply into God’s touch that it is overcome by all its craving, and it is reduced to nothing in all its acts.

It seems that God’s touch embodies a simple act of amnesia: to forget It even as It forges a relationship with man. Inner practice is about forgetting all contingencies as it charts a course towards ‘His fathomless love,’ the one-foldedness of his divine nature. All of this allows John to see primal Reality, or deity itself, bearing a two-fold character, of the one and the many. Though it must be said that for a mystic like himself, its realization is partly a synthetic experience: it must be through thought analyzed in a particular mystical way, if it is ever to be grasped. God, as known by man, exhibits in Its perfection in these dual properties of Love – that is, the one and the many – while at the same time It continues to be active, generative, and creative.

Such a melding of duality and unity for John becomes an ineffable possession, which he calls a Fruition. It is one of Ruusbroec’s master-words. God is, then, the Absolute One in whom the antithesis of Time and Eternity, of Being and Becoming, are finally resolved. God transcends the storm of succession, yet at the same time is the inspiration behind flux itself. According to his fruitional nature, God works without ceasing, for ‘He is pure act.’ He is the omnipotent and ever active creator of all things, an immeasurable ‘Flame of Love’ perpetually breathing forth energetic life in new births of being and new floods of grace. Thus the world of nature, none other than John’s beloved trees, participate in this fruitional encounter with deity.

What makes a man bury himself in language in such a remarkable way, one might ask? What makes him put aside rapture in order to render it as words? I confess that I am shaken by his intensity of expression when it is raised to such fever pitch. I try to imagine what it must have been like for John to live his secluded life at Groenendaal, attending to his duties as a prior, yet ever able to explode with such mystical fervor when alone.

A single fathomless word he hears, and nothing more. Yet it is this word, he knows, that God uses to utter Himself without intermediary and without cease. The word, John contends, is the verb ‘to see’. And this ‘seeing’ embodies the going-out as well as the advent of Christ as a beam of ‘eternal light’ directed towards him. Seeing becomes the birth of a rusticated love in the forest determined by nature as visionary cohort. Being seen in such a way, John himself becomes an enormous eye, a cosmic eye, ranging across the entire earth. Moreover, his eyes become as changeable as mercury in a bowl, an intense yet malleable presence confronting the enormity of the cosmos. He is enthralled. Finally he begins to perceive the inner activity of Being itself.

The first point and foundation of all spiritual life is to enter a state of ‘bare imageless being,’ says John in his masterpiece, The Sparkling Stone. Only then can one become a ghostly man. In doing so, one becomes effaced by the knowledge that in order to reach a point of ‘indwelling and divine enjoyment,’ it is necessary to understand the language of stone. Fundamentally, he believes, language is shaped out of silence. To be a mystic is to reach out to silence. And stones, for the most part, are silent. A mystic is always trying to formulate a language that is shaped by an un-articulated silence. As Apollodorus of Athens remarked, ‘Silence honors the gods by imitating their nature, which is to escape meaning.’ The mystic’s task is therefore to find a way to escape meaning. He does so by entering that privileged place that is silence. The mystic, like the poet, has only two choices: either to look at things, or to be in them. Unlike the poet, the mystic invariably chooses the latter.

He feels the horizon of absence and unreality whenever he engages with rapture. In the course of his meditations he runs aground on the shore where he expected to arrive much later, that of his own annihilation. John must have known this feeling early in his vocation as a mystic. One senses that his retreat into the forest around Groenendaal was his way of managing the effects of his estrangement from things as that of being real. Clearly the stoniness or woodiness of things spoke to him. He listened to their individuation as things, their struggle to affirm existence by way of the non-conversation that he had with them. They were, so to speak, like steles or cicatrices, registering their ‘marks’ upon his consciousness. For him, language had become one of nature’s hieroglyphs.

I will give him a small sparkling stone, and in this stone a new name written which no one knoweth, except him who receiveth it. That stone is called a pebble, because it is so small that it will not hurt a man, even if he treads it underfoot. The small stone sparkles brightly, and it is red like a fiery flame. It is small and round and smooth and it is very light.

This is the way stones speak to John of Ruusbroec. The sparkling stone is none other than Jesus Christ. Why, one might ask? According to John, such a stone is known as a ‘calculus’, which is a small measuring stone used in computation. By extending his metaphors, he is able to suggest that this stone’s smallness relates to that of Christ when he humbled himself, and allowed himself to die on the cross. ‘I am a worm and not a man, the scorn of men and an outcast of the people.’ Christ had made himself so small that Jews were able to tread on him – he, the sparkling stone of divine truth. Ruusbroec cannot put down the image; it fascinates him:

The last feature of the stone I would like to speak of is that it is very light, for the Father’s Eternal Word has no weight, and yet carries heaven and earth in its power. It is equally close to all things, and yet no man can overtake it, for it transcends all creatures. It takes precedence over them all. Moreover, it will release itself to those who it chooses, and where it chooses. Now its lightness, our heavy human nature, has gone beyond all the heavens, and sits crowned at the right hand of the father.

Contrasting ‘heavy human nature’ with the sparkling stone is one of John’s verbal triumphs. Possessing the latter, that is, the sparkling stone, enables a man of contemplation to receive a new name, which is the door to living a mystical life. No one knows this secret name other than he upon whom it has been bestowed. This secret name of transcendence is a gift to all those who bear the tiny pebble of Christ in their innermost being. Ruusbroec urges us to protect the stone within us if we wish to live a ghostly life:

You must know that all spirits are given a name as they return to God, and each in accordance with the nobility of its service, and the high nature of its love.

The concept of waylessness, John later tells us, alluding of course to Christ as the Way, is the object or passage towards the mystical life, since only Christ ahs lived it. To pass into the presence of God, one must be wayless. It is the ‘glorious wandering in the Super-essential Love wherein neither end nor beginning, nor way nor manner, can ever be realized.’ For John this is a simple death-like passing, an annihilation of identity and ego. To be bare and wayless is to love consummately and without reserve. It is the perfect counterpoint to a life lived under the aegis of ‘Reason and in Ways.’ People who live in this “wayless way” become ‘secret friends, the hidden sons of God.’ Selfhood has been discarded like a worn-out coat. Then we are ready to gaze into our super-essence, and so receive, deep within us, a scintilla of God’s essence in the form of our soul’s growth. The ‘deep quiet’ of Godhead becomes a ‘simple and abyssal tasting.’ Living the God-seeing life, we feel ourselves to be living in God. From out of that life ‘there shines forth on the inward face of our inward being a brightness that enlightens our reason as an intermediary between ourselves and God.’

Once more we are awash in the healing poultice of language. John of Ruusbroec is taking us to a place where few men have been. It is not so much a difficult place to find; rather, it is a place that is defined by the apophaticism of language itself, the pure negativity of words. It is as if words have the power to negate being, to be without being, and therefore owe nothing to being. To be released from being is the ultimate quest of the mystical thinker. He is free when he is released from his I-am-ness, and so denatured of his right to be. In him at this point the whole of humanity is embodied. The mystic stands within and above history at that moment in time.

Solitude becomes his companion, given that he exists outside normal contingencies. Free of being, so to speak, and separated from beings, the absolute I-am affirms itself in a supra-personal way, and without reference to others, except in a nominal way. In the process, a solitary holds himself back from nothingness, as did John of Ruusbroec. Through his waylesssness he found a way to negate being, yet allow it an existence that is both transcendent and real. As Holderlin remarked, one must preserve God through the purity of what distinguishes. Ruusbroec struggles with this challenge. He knows that his language is inadequate to that which he has witnessed under a tree in the forest. His rapture has become embroiled in the struggle to find adequate images to render it palpable to others.

To escape into non-being is the object of his quest. Non-being is a part of God, he knows that. Therefore he is trying to escape into God, as he feels himself drawn towards, and into Him, by His Love: ‘…for as long as we inwardly see that God wants to be ours, God’s generosity will touch our greedy lust, and this causes restlessness of loving, for God’s touch that flows out of us fans our restlessness and demands our action, namely that we love the love eternal.’ ‘And this touch that draws us inward makes us feel that God wants us to be His, for in it we must deny ourselves and allow Him to achieve our bliss. But where His touch flows out of us He leaves us to ourselves and makes us free…’ According to John, this is the crux of God’s argument: that He wishes to achieve our bliss through our denial of ourselves. The loss of self gives God the opportunity to join with us in a state of bliss.

One of Ruusbroec’s most important contributions to mystical thought is his concept of modes. Without modes, he says, no one can live. Modes are delineations and distinctions, categories of action and thought. Weights and measures are also modes. Reason is a mode. So too is sobriety. Discretion as well. However, too much engagement with what John calls ‘multiplicity of heart’ leads to an inability to invoke its contrary, none other than a state of modelessness. People become too busy about their needs, too entrenched in their modes, believing these to be sufficient to the cultivation of their inner life. Relying too much on their external senses makes it impossible to find inner satisfaction. Provident discretion is good, he says, whereas engaging in too many cares or modes for their own sake is unwise. Moreover, being ‘full of images’ of alien things, prevents contemplation or being in a state of modelessness.

For John, contemplation is the true way to knowledge. It is the basis of all his thinking with regard to the mystical life. Why? Because it is a “modeless knowing”. In his prefatory poem to the Beguines, he makes it possible for us to comprehend the power and beauty of his mystical engagement with God:

Contemplation is a modeless knowing

Which always remains above reason.

It cannot descend into the reason

And reason cannot reach it above itself.

Enlightened modelessness is a sublime mirror

In which God lets his eternal light shine.

Modelessness is without manner,

In which all work of reason fails.

Modelessness is not God,

But it is the light in which one sees.

Those who walk in modelessness, in the divine light,

See into the void.

Modelessness is above reason, not outside it;

It sees everything without amazement.

Amazement is below it:

Contemplative life is without amazement.

Modelessness sees, but it knows not what:

It is above all neither this nor that.

Now I must leave rhyming behind

If I shall clearly describe contemplation.

Here we find ourselves in the presence of a luminous mind contemplating essences in a state of pure unreason. When a person achieves such a state of pure modelessness, a state of what John calls ‘modeless love,’ and has acquired the capacity to be annihilated, only then is he able to melt away in love, and so become deiformed – that is, to be transformed into the image of Christ. By way of comparison, he alludes to a red hot iron manifesting all the properties of the fire. ‘As far as it is fire it is iron, and as far as it is iron it is fire. Nonetheless, the iron does not become fire nor the fire iron.’ Each maintains the integrity of its own matter and nature. Likewise, John says, the human spirit does not become God; but it is given the form of God. Thus a person becomes deiformed. He understands himself to be uplifted to the level of God. He sees himself as part of God’s ‘depth’, and so uplifted in his own super-essence, which is none other than God’s essence.

Once more John tires of seeking out the dilemma that lies at the heart of language when it is deliberately subjected to the impress of mystical fervor. He is utterly unable to resist this unfathomable dialectic, given his love of the verbal construct in language itself. One senses that Ruusbroec is drawn to it as iron is to the fire. Nor can he escape the heady vortex of thought that it implies. He longs to be lost in language, to be smothered in the silkiness of words. They are more real to him than what the world offers. He is framed by the mystical artifice of letters. They are like butterflies, dancing above the meadow of his mind. From them he formulates ‘humble lowliness,’ ‘unmoved blessedness,’ ‘imageless inactivity,’ ‘eternal lostness,’ and ‘imageless nudity’ as but a few of his radical new concepts. These become talismans for John of Ruusbroec. He has found a way to break down language into its component parts, and then rebuild these as he would have them appertain to what he calls the ‘imageless mind of God.’ He wrestles, he fights until he begins to feel unity ‘without difference or distinction,’ even as he resorts to language to express what he means. The mystical life has become a state of ‘fruitive love’ for him in all its aspects.

John of Ruusbroec was one of the great mystical geniuses of his age, indeed of any age. He wrote more treatises than either Meister Eckhart or Therese of Avila during his long life. One is constantly amazed at his output at a time when paper and time were at a premium. Nor had the printing press been invented. Who did he write for? Certainly not for the general public, which would have found his thought all but incomprehensible. He wrote for the few, his confreres in the monastery and to those whom he knew from elsewhere through his letters.

Here is a man who radiated words. They were a manifestation of his light. In him the mystical life reached its zenith. Through him it became a composed method of spiritual growth for men long used to the oppressive imperialism of theology in their lives. John, along with his friends, John Hinkaert and Francis van Coudenberg, together they served notice on the old monastic system by founding their priory of three at Groenendaal, at least initially. They were in the vanguard of a more private order of devotion, one committed to the individual’s response to the divinity of Christ. Grote, Tauler, and Thomas a Kempis were deeply indebted to his writings in their desire to further develop the Modern Devotion movement in Germany and the Netherlands.

The effect of his thought is far-reaching, even down to our own time. Modern Dutch poets such as Leo Jansen and Hans Vandervoorde fashioned their own mystical perception through reference to Ruusbroec’s imagery. Henry Michaux, another Belgium writer and surrealist (1899), was deeply influenced by his compatriot. When he wrote ‘I write with transport and for myself,’ we could be hearing the voice of Ruusbroec himself. He spoke of the act of writing as an exorcism, deliberately so. Without God, however, writers like Michaux could only resort to the nostalgia for nothingness in their bid to find meaning in their lives. It became harder for these modern writers to invoke the mystical life, except elliptically. The notion of living in Christ had been subverted by secularism and the modern condition. For Michaux, as for other modern writers, such a life became an oddity.

Finally, we must confront John of Ruusbroec’s unique use of language if we are to understand his importance to mystical thought. He has made the world of neologism his domain. His mysticism is the result of a leap into the unknown. No writer can match him in this respect, not even Eckhart, for the way the use of neologism managed to help him express the sublimity of his thought. He has provided the inexpressible and the mysterious with a syntax of its own. Christ’s memory is well served by him, and we should be grateful. It remains to be seen whether his voice will be heard in our own age, where the reign of facts hold such sway over our lives – much more than his gentle empiricism of the spirit.

An uneventful life, and yet a life lived with inner fervor. We are attracted to John of Ruusbroec precisely because, unlike a mystic such as Angela of Foligno, he did not appear to live an openly conflicted life. The forest around his hermitage offered him its protection, its path towards the mystical life. He found a way to make its natural introversion a part of himself. Pure, one-fold clarity became the preserve of this – as he spoke of himself – utterly ghostly man. What was shadowy in his personality, what he called his lack of modefulness, remains, even today, the essence of what he was as a mystical thinker. He found a way to abandon language, even as he embraced its mindfulness.

All things

are too small

to hold me,

I am so vast

In the Infinite

I reach

for the Uncreated

I have touched it,

it undoes me wider than wide

Everything else is too narrow

You know this well,

you who are also there

Hadewijch (13th Cent.)

This is the man who penned The Sparkling Stone and The Book of Supreme Truth. Both books are late-medieval spiritual classics that reflect a startling grasp of the apophatic nature of philosophic expression which had crept into Christian theology after the translation of Dionysius the Areopagites’ Divine Names and Celestial Hierarchies by John Scotus Erigena in the tenth-century. Ruusbroec’s work represents a development of mystical concepts appropriate to an age that had already fully absorbed Neoplatonism and the works of Aristotle. Contemplation, the monastic ideal, and a greater understanding of the ethical requirement of an age much afflicted by disease and political disruption meant that Ruusbroec’s vision was of special relevance. He had fashioned a language, an apophatic language, in order to bear the weight of a new dispensation that was about to burst upon the world. The humanists of the Renaissance, particularly in Italy, owe much to this man’s pioneering work. They were free now to put aside mystical exegesis in their pursuit of the life-loving gifts of classical Greek philosophy. Because of his deep spiritual insights, men like Marsilio Ficino and Francesco Guiciardini could embrace Plato and Aristotle in a new and refreshing way.

Ruusbroec represents the beginning of a modern subjectivity with regard to the inner life. Though he was deeply conventional in his dogmatic understanding of the tenets of Christianity, he nonetheless found a way to circumvent these by resorting to a mystical language that released Christian dogma from its age-old constraints as a repository of piety and ethics. His Christianity, aligned to metaphor and poetry as it was, heralded a revival of mysticism as a spiritual practice that all men could partake of. Now a believer could find solace in his own thoughts rather than simply rely on clerical advice or admonition. The seeds of humanism had been planted, and John of Ruusbroec tended them with love and forbearance throughout his life. In his hands the ‘sparkling stone’ of the mystical way had been fashioned into a rare and precious gem. We must be thankful for his quiet and retiring genius in enabling this to happen.

James Cowan